ʻUla ka moana i ka ʻahu ʻula a me ka mahiole: the Ocean is made red with feathered cloaks and helmets

“Kauluwela ka moana i nā ʻauwaʻa kaua o Kalaniʻōpuʻu. Aia nā koa ke ʻaʻahu lā i ko lākou mau ʻahu ʻula o nā waihoʻoluʻu like ʻole o kēlā a me kēia ʻano. E huila ʻōlinolino ana nā maka o kā lākou mau pololū me nā ihe i mua o nā kukuna o ka lā.”[1]

The sea glowed brightly because of Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s swarming fleet of war canoes. The warriors were dressed in feather cloaks of all different colors. The points of their long spears and javelins flashed brightly before the rays of the sun.

I can only imagine what it must have looked like, an ocean colored by millions of delicate feathers. If I close my eyes, I can picture the deep reds and bright yellows draped across the backs of our ancient chiefs. I can see them; I can feel them.

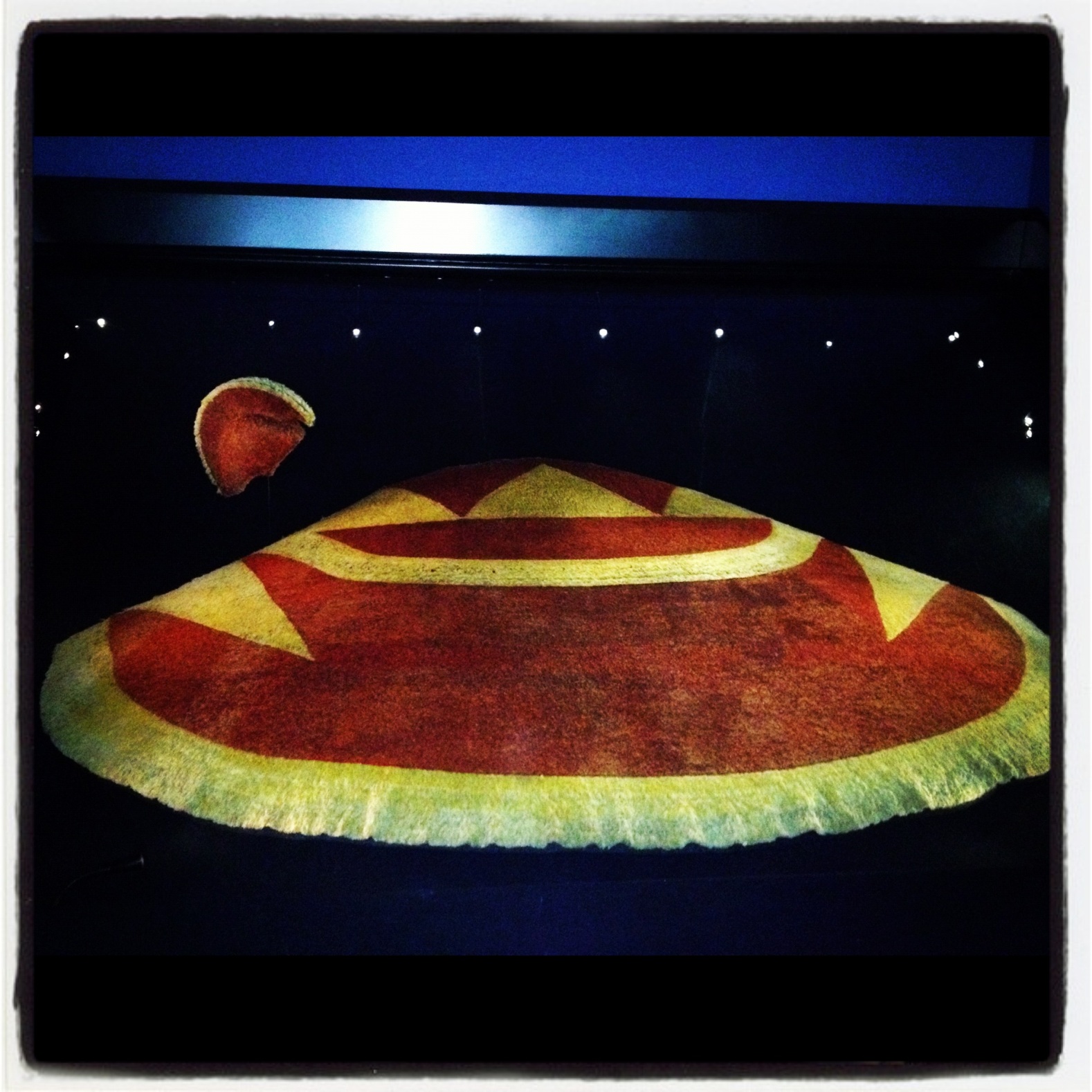

Yesterday, I sat a few short feet away from Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s ʻahu ʻula and mahiole, his feathered cloak and helmet. And as they lay before me, I closed my eyes for a brief moment and pictured them in movement, pictured them on the body of our chief, pictured their tiny red and yellow feathers on an ocean, rustling in the wind, full of life. I could see them; I could feel them.

So I whispered a small greeting, as I have many times before, and as the hours passed and as the space around me filled with chants and songs, with the familiar sounds of ʻōlelo and te reo mixing and rolling off tongues, the wind shook the whare and I said my goodbye.

It was like saying goodbye to a loved one, to a family member, one who I knew I would see again, but one that I would miss terribly. They would be going home, back to Hawaiʻi, back to our people, back to our lāhui. And as I sat there, I could not help but shed tears for all that they have come to mean to me, for all that they have inspired in me, for all that they will continue to inspire in my people.

Today I continue to shed tears as a write, carrying an emotion that I cannot quite describe: a mix of extreme gratitude and deep aloha, a mix of happiness accompanied by hope, and on a very personal level, a mix of protectiveness deepened by a sense of responsibility. Although I know that my story is small in the larger history of this remarkable cloak and helmet, I share it because I feel compelled to do so, perhaps as a means of bringing our attention back to them, to these taonga, these treasured items, these mea makamae, to their lives, to their journey, to their future.

Much has been said in the past few weeks about the return of Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s cloak and helmet: some are in support of their journey home while others are not, some are worried about their new association with certain state organizations, and some are concerned that they will be placed at the center of what has become a heated (and sometimes ugly) political terrain. I appreciate what has been said and shared. It has inspired debate and dialogue, which is extremely important. And while this may or may not add to the conversation, I write this because I feel a responsibility to do so: to honor them, to look after them, to love and care and celebrate them for the impact that they have had on generations of people.

When our Hawaiian scholars took to the newspapers in the nineteenth century to record the lives of our ancient chiefs, they described their exploits and adventures in detail, as if each small event was like a tiny feather, seemingly insignificant on its own, but in context, completely necessary. One such writer was Joseph Poepoe who, between 1905 and 1906, recorded the story of Kamehameha in the Hawaiian language newspaper named for the famous chief, Ka Naʻ Aupuni. While writing about Kamehameha and his celebrated uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, he described many battles, looked at prophecy and strategy, highlighting training and skill. And in his descriptions, he also spoke of the sight of ʻahu ʻula and mahiole. When warring chiefs traveled over cliff sides, they turned the land red with ʻahu ʻula. And when they boarded their war canoes, “ʻike maila i ka ʻula pū aku o ka moana i nā ʻahu ʻula a me nā mahiole” their opponents saw the ocean turn red with feathered cloaks and helmets, with millions of tiny red feathers.[2]

I can only imagine what they must have thought, what warriors must have thought when they saw their cliff sides turn red with soldiers and chiefs adorned in ʻahu ʻula and mahiole. And I can only imagine what it must have been like to watch the ocean go red. While I cannot say for certain what they must have felt, I am sure that it inspired something, whether fear and dread, whether hatred and anger, or whether even awe and a bit of amazement. I’m sure they saw them; I’m sure they felt them.

Two hundred and thirty seven years ago, Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s ʻahu ʻula and mahiole were gifted to Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay. Although Captain Cook never left the island, these treasured items did, making their way aboard ship to England where they were viewed by thousands in a strange land. What curiosity they must have inspired. Perhaps they became tokens of a far away place and culture, a “far away” people. Perhaps they too were exoticized, romanticized, or perhaps even degraded and disrespected. Perhaps they weren’t. While I am not sure what an English man or woman must have thought looking at the deep reds and bright yellows of our chiefs, or what reactions would have been stirred within them, I am sure that they must have stirred something.

While they were away, things changed, lives in Hawaiʻi changed. After the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, a writer in the Hawaiian language newspaper, Ke Aloha ʻĀina, seemed to lament the fact that some of their people had never seen an ʻahu ʻula, perhaps a mahiole, or even other chiefly symbols like kāhili, feathered standards. Thus, in 1901, an invitation was put out for people to go to Wakinekona Hale, the home of the deposed Queen Liliʻuokalani, to see them: “E hōʻike i ko kākou aloha aliʻi ʻoiaʻiʻo i mua o nā malihini o na ʻāina e e noho pū nei i waena o kākou, i ʻike mai ai lākou he mea nui ka Mōʻīiwahine iā kākou, kona lāhui.”[3] The article states: “Let us show our true love for our chiefs in front of all of the foreigners from other lands who now live amongst us, so that they will see that our Queen still means a great deal to us, her nation.”

For a people learning to live with the overthrow of their Queen and the subsequent illegal annexation of their kingdom to the United States, I can only imagine what the sight of an ʻahu ʻula must have inspired in them: honor and gratitude, sadness and longing, or perhaps love and a deepening commitment to aloha ʻāina, a renewed and inspired sense of patriotism. Generations prior, ʻahu ʻula turned oceans red; they covered hill sides as warriors marched to battle. They adorned our chiefs and stood as symbols of rank and mana. In 1901, however, it seems that their appearances in public became rare. Thus, to view a cloak and helmet then surely must have stirred something.

In 1912, when Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s ʻahu ʻula and mahiole were unexpectedly gifted to New Zealand, they became part of the national museum’s collection and have been here since. I write this from New Zealand, in the country that they will leave in a few short hours. When I first came here nearly four years ago, I knew that I had to visit them. Thus, on my second day in the country, I went to Te Papa Tongarewa and found them tucked into a dark space in the museum, alone and somewhat separated from everything else. After that day, back in 2012, they became my personal puʻuhonua, my personal site of refuge and safety in a new place thousands of miles from home. I visited often, whenever I needed a piece of Hawaiʻi, whenever I needed to reconnect, to recenter, or to find guidance. I talked to them and I shared my life with them, imagining that if I felt lonely so far away from home that perhaps they did as well. They stirred something in me then; they stir something in me still.

A little over a week ago, I stood next to the ʻahu ʻula and mahiole, chanting before them, to them, and around them in anticipation of their upcoming departure. And as I chanted, I pictured the moana, the ocean that they would once again cross. These sacred symbols of our chiefs would be making their way home, not by waʻa, but by plane, leaving a trail of histories along the way, turning the ocean red once again, this time with ancestral memories. Standing there next to them, as I had many times before, I thought about my many visits. Since moving here, I have learned to cease thinking of them as relics from the past, but have come to embrace them as pieces of our past that have lived to the present and that stir our hearts and minds contemporarily. I see them; I feel them.

Thus, for one last time, I marveled at their beauty and at the skill of my ancestors, and as I stood there, thinking about our history, I realized that each generation of people has seen and understood them differently, always revealing something about the times in which they lived. What a Hawaiian in 1779 must have thought at the sight of an ʻahu ʻula and mahiole—treasured items that were apparently so abundant that they could turn oceans red—would have been drastically different than what a Hawaiian in 1901 would have thought, just a few short years after the illegal annexation of Hawaiʻi. And these reactions and inspirations are different than what filled me when I first lay eyes on them, a contemporary Hawaiian woman who was raised in the years following the Hawaiian Renaissance, who was raised with hula, who was raised to value ʻāina, and who was raised to be an aloha ʻāina. My interpretation of them will always be a product of the present, of who and what we are now, of where and when we happen to be today.

That brings me back to today. I think about these mea makamae and all that they mean to me, and I shed tears once again for what they will come to mean for all of those people who will now get to greet them, to welcome them home, and to embrace them as I have here. They have inspired a range of emotions and reactions throughout the generations. Therefore, while I cannot say what they will bring out of those who will get to see them and visit with them, I am sure that they will stir something: perhaps a sense of hope, perhaps a dream of unity, perhaps a remembrance of strength and pride, perhaps a sense of kuleana. I look forward to seeing what they will come to represent, what they will teach us about ourselves, and how we will continue to talk about, write about, speak, sing, and dance about their existence as a means of further exploring our own.

I can only imagine it. So, I close my eyes once again, picturing them in movement, imagining an ocean made red. They have been two of my most profound teachers in the last four years. They have taught me of responsibility; they have taught me of honor, respect, and humility. They have taught me to consider all that we can do and all that we will do, to leave our mark on history. My efforts may not be as great as Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s, or my story as grand. However, when I looked at them yesterday, as the ceremonies and protocols were being carried on around me—in a mix of Hawaiian and Māori customs—I smiled, quieted my head and heart, and blessed their journey across the ocean, this time perhaps as a reminder of ʻula, of the red that can and shall unite us

E ʻula pū ana nō ka moana i ka ʻahu ʻula.

References:

[1] Poepoe, J. (1905, 7 Dec.) Ka moolelo o Kamehameha I: Ka nai aupuni o Hawaii, Ka Nai Aupuni, p. 1.

[2] Poepoe, J. (1906, 12 Sep.). Ka moolelo o Kamehamea I: Ka nai aupuni o Hawaii, Ka Nai Aupuni, p. 1.

[3] He ike alii nui i ike mua ole ia ma hope mai o ke kahuli aupuni (1901, 24 Aug.). Ke Aloha Aina, p. 1.